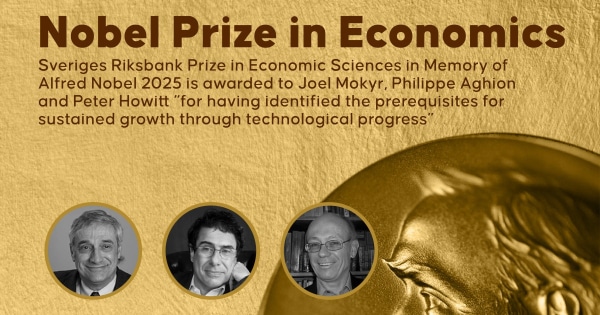

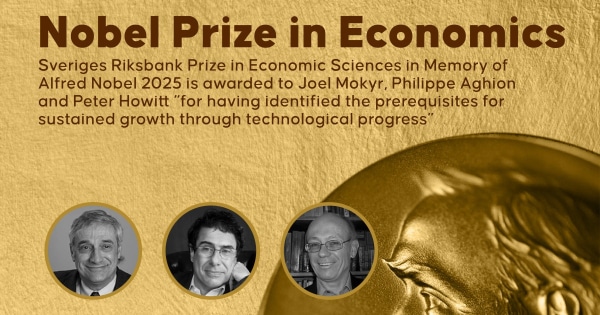

““`html The 2025 Nobel Prize laureates in economics, Joel Mokir, Philip Aghion, and Peter Howitt, bring together different perspectives on the analysis of the determinants of economic development, focusing in particular on the roles of culture, innovation, and competition. How can societal ideas and economic competition underpin sustained economic progress? And why? Ukrainians and the Ukrainian language […]”, — write: businessua.com.ua

The winners of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics, namely Joel Mokir, Philip Aghion and Peter Howitt, bring together different perspectives on the analysis of the determinants of economic development, in particular, emphasizing the role of culture, innovation and competition. How can ideas formed in society and economic competition serve as the foundation for long-term economic progress? And why is it extremely important for Ukrainians and the Ukrainian authorities to become “inquisitive”? Review of the study of Nobel laureates by the senior officer of the staff of the 2nd building of the NSU “Charter” and the professor of practice of the Kyiv School of Economics KSE Pavel Sheremety

Purchase an annual subscription for six editions of Forbes Ukraine by value four. If you value the quality, depth and power of practical experience, given subscription just for you

It would seem that the question “How does the economy progress?”, for which three scientists received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2025, should be central to the thinking of mankind for millennia. But if economic theory as such is a fairly young science, then it systematically formulated the question of economic uplift even later, only 100 years ago.

Four approaches to understanding “how the economy grows” “For decades, modern economists have sought to understand growth in four different ways,” states British economist Daniel Susskind in his work Growth.

popular Company Category Date Yesterday $30 million on music videos for Apple and Coldplay. Darko Skulsky turned radioactive video production into a favorite of global brands. How did the war affect his activities?

First, there were those who tried to reproduce the large-scale vision of classical social theorists by creating large, comprehensive narratives. Then there were mathematicians who developed more restrained, clear, highly simplified models, limiting their attention to well-defined features of the world that they considered important.

Third, there was the approach taken by the data processing experts by referring to historical evidence. Among them is Nobel laureate Semyon Kuznets, who studied in Kharkiv at the beginning of the 20th century.

And finally, there were the fundamentalists, united not so much by a common methodology – social theory, mathematics, or data science – as by a common interest in finding ever more fundamental explanations. For example, Joseph Schumpeter, who wrote his relatively concise, but fundamental “Theory of Economic Development” in 1910 during his teaching career at Chernivtsi University.

“These four ‘tribes’ climbed to the same intellectual peak, trying to understand the reasons for the rise, but they took different paths to the top,” Susskind summarizes.

Culture as a basis for growth If this year’s laureates Philip Aghion and Peter Howitt can be counted among the second “tribe” of mathematicians, then Joel Mokir is an economic historian and belongs to the fourth “troop” – fundamentalists.

Last year’s winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics – Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson – proved that the quality of institutions is important for economic development. Joel Mokir argues that culture is also decisive.

Mokir’s main idea is that modern economic prosperity stems from the historical evolution of a culture that systematically formed, tested, and implemented useful knowledge, transforming curiosity into productivity. Curiosity for him is not just a psychological trait; it is a cultural and institutional phenomenon that has made constant innovation possible.

Mokir argues that technological progress, not just capital accumulation or population growth, is the real driver of sustained economic progress. In this, he and his two fellow laureates are clear representatives of the school of endogenous (internal) economic growth, largely unknown in Ukraine, which has “stuck” in the paradigm of exogenous (external) growth due to the increase in external factors – capital and labor.

For this reason, we continue to talk so much about the need for investment, primarily foreign (this is already a big mistake, since foreign investment in the world is barely 3% of all investment), the return of refugees and the attraction of migrants. And we almost do not mention the need to increase our catastrophically low total factor productivity (first of all, through innovation and technology), which is exactly what this year’s and many other Nobel laureates emphasize, such as, for example, Robert Solow.

This American economist proved back in the middle of the last century that the vast majority of economic development – 87.5%, to be exact – was caused by something other than an increase in investment or labor.

And Solow assured that “this “something” should be technological progress: in other words, growth did not occur due to the use of more resources, but due to the more productive use of these resources.”

This is extremely important for Ukraine, because according to the data of the authors of last year’s report on world development from the World Bank, which they presented at the Kyiv School of Economics and to which both Aghion and Ajemoglu joined, before the war, the physical and human capital in Ukraine was 133% of the American capital in relation to GDP. However, total factor productivity in Ukraine was only 17% of the American one.

Technologies are not just mechanisms For Mokir, technologies are not just mechanisms, but the “useful knowledge” behind them. “The Industrial Revolution did not start inventions, but it did start the ‘method of invention’, transforming it ‘from an occasional event to a regular and habitual part of the economy.’

Mokir wonders why the industrial revolution began in Europe, and not, say, in China, which was economically and technologically more developed in the Middle Ages, and studies for this purpose, in particular, the period of 1500-1700 years. He argues that the political fragmentation of Europe encouraged a competitive “marketplace of ideas” and a desire to explore the mysteries and laws of nature.

“If a single centralized government were responsible for protecting the intellectual status quo, many of the new ideas that eventually led to of the Enlightenment, would have been suppressed or perhaps never even offered,” Mokir writes in his book, The Culture of Growth.

In this, Mokir continues and concretizes the logic of another Nobel laureate, Paul Romer, the intellectual founder of the theory of endogenous development.

Romer’s works were revolutionary. As well as another Nobel laureate in economics Robert LucasRomer and Mokir turned their analysis away from the physical, “tangible” realm of the economy. But Romer’s shift was much larger: instead of focusing, like Lucas, only on the skills of workers, Romer moved entirely from the world of material objects to the world of immaterial ideas. In doing so, both Romer and Mokir used the work Lucas had done on human capital, making it only a minor part of a much bolder narrative.

After all, what is human capital but the ideas in people’s heads?

The pairing of Joel Mokir for the 2025 Nobel Prize with Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt is no coincidence: the three represent two complementary aspects of a single grand theory – a wholly endogenous, Schumpeterian vision of development that encompasses everything from culture to competition.

While Mokir focuses on the sources of useful knowledge, Aghion and Howitt focus on the dynamics of how innovation drives development.

If Mokir sees the mechanism of development as the cultural and institutional evolution of curiosity, science and technology, then Agion and Howitt see economic competition and Schumpeterian “creative destruction” among companies.

In other words, Mokir explains WHY societies form ideas, while Aghion and Howitt explain HOW these ideas drive uplift through economic mechanisms.

I studied Philippe Aghion’s book The Power of Creative Destruction in great detail as soon as it came out back in 2021, and I’ve been quoting from it in almost all of my speaking engagements.

“Creative destruction is a process by which new innovations continuously emerge, rendering existing technologies obsolete; new companies constantly appear to compete with existing ones; new jobs and activities are emerging that replace existing ones,” writes Agion.

Creative destruction, creating risks and shocks that need to be managed and regulated, “is at the same time the driving force behind capitalism, ensuring its constant renewal and reproduction.”

“`

The source

Please wait…