“How to make the support of veterans high-quality.”, — write: www.pravda.com.ua

This shift in focus from spaces to people is no accident. It reflects deeper changes in approaches to veteran policy, which took place at the international level and did not bypass Ukraine. There are only five countries in the world that have the profession of veteran support specialist: USA, Canada, Great Britain, Australia, Germany. In November 2024, Ukraine joined them, becoming the sixth.

This transformation is the emergence of a new profession — a logical response to the challenges of time. Veteran support specialists are navigators in services for veterans. After all, there are more than a hundred available services, both at the national and local level. And understanding how to use them becomes a separate specialty. Often, these people have the appropriate status themselves, or are members of military or veteran families. Faced with their own experience with questions from the field of veteran services, they become guides for others.

Advertising:

Currently, this field is mostly occupied by enthusiasts who are ready to learn on their own, master the intersection of legal, medical, social issues and collaborate with other specialists to gain experience. They often have a good idea of what services should be available to veterans, but are faced with system imperfections, even at the level of basic information. The same applies to family doctors, who can act as navigators for veterans in the field of medical services.

However, even with the presence of such specialists, the veteran support system remains fragmented.

According to the results of the recent research IREX, more than 60% of veterans have never sought psychological help. Often not because they don’t need it, but because they don’t know where to turn or don’t trust the system. Only a third of veterans say they have access to medical support, and one in six didn’t even know it existed. It’s not about the lack of walls. First of all, it is about the lack of service infrastructure, namely people, processes and competencies at the community level. At the same time, it is a complex story, where the main framework is set at the national level. Despite significant progress in the expansion of services, there are still many questions regarding their implementation.

According to the data of the same study, the majority of veterans, when receiving services, prefer not to seek help from state or municipal institutions, but from their informal circle— family, siblings or stepsisters, acquaintances or friends. Sometimes they don’t have big facades, but there is trust built up over the years. It is they who promote real reintegration, when you don’t need to ask without waiting in line to “just ask”, but you can get support quickly in your community: in person, by phone or online.

Physical infrastructure is indeed a symbol of state presence, but war makes these symbols vulnerable. In the frontline regions, the communities have already understood: it is possible to restore a destroyed building in a few months, and to train a specialist is an investment that works for decades. What can we say about the relocated communities, where it is this person who is the bridge between the native city and the residents of the occupied settlements scattered around Ukraine and the world.

A psychologist, social worker, lawyer, career counselor is an “invisible” infrastructure that cannot be destroyed by a rocket and that remains with a veteran where they live.

IREX recently organized and held a strategic session with veteran policy stakeholders, which included representatives of the state, communities, public organizations and businesses. And precisely the problem of lack of service capacity at the level of service providers was identified as one of the top 3.

During the discussion, the participants unanimously noted that the main challenge is not to create new physical centers, but to ensure sustainability and quality of services, regardless of where they are provided. The focus should be on the person, not the building.

In order for this to become possible, the state should expand approaches to the procurement of services. In veteran policy (but let’s be honest – not only in veteran policy), the need for procurement mechanisms for social, legal, psychological, educational and rehabilitation services from non-state providers is ripe. Organizations that already have experience, teams and trust among veterans.

This is not a question of privileges for public organizations, it is a question of quality. This model already works for some services in the social sphere, in addition, the Ministry of Veterans Affairs pays psychological service providers for work with veterans. However, it seems time to apply the same model to legal and rehabilitation services.

For example, I see no problem in contracting a public organization in a remote community that will perform the function of a system of free legal aid bodies. And mobile teams from public organizations not only reach hard-to-reach regions, but also show a 100% level of service satisfaction among veteran clients.

We still have time to prepare systems and specialists who will work alongside veterans. Investing in this means forming local service ecosystems, teams of specialists in communities that can be integrated into existing TsNAPy, hospitals, employment centers, BPD or the same veteran spaces.

Perhaps the best physical wall for veterans in the near future may not be concrete, but a network of those who are already nearby and live in the same community with them.

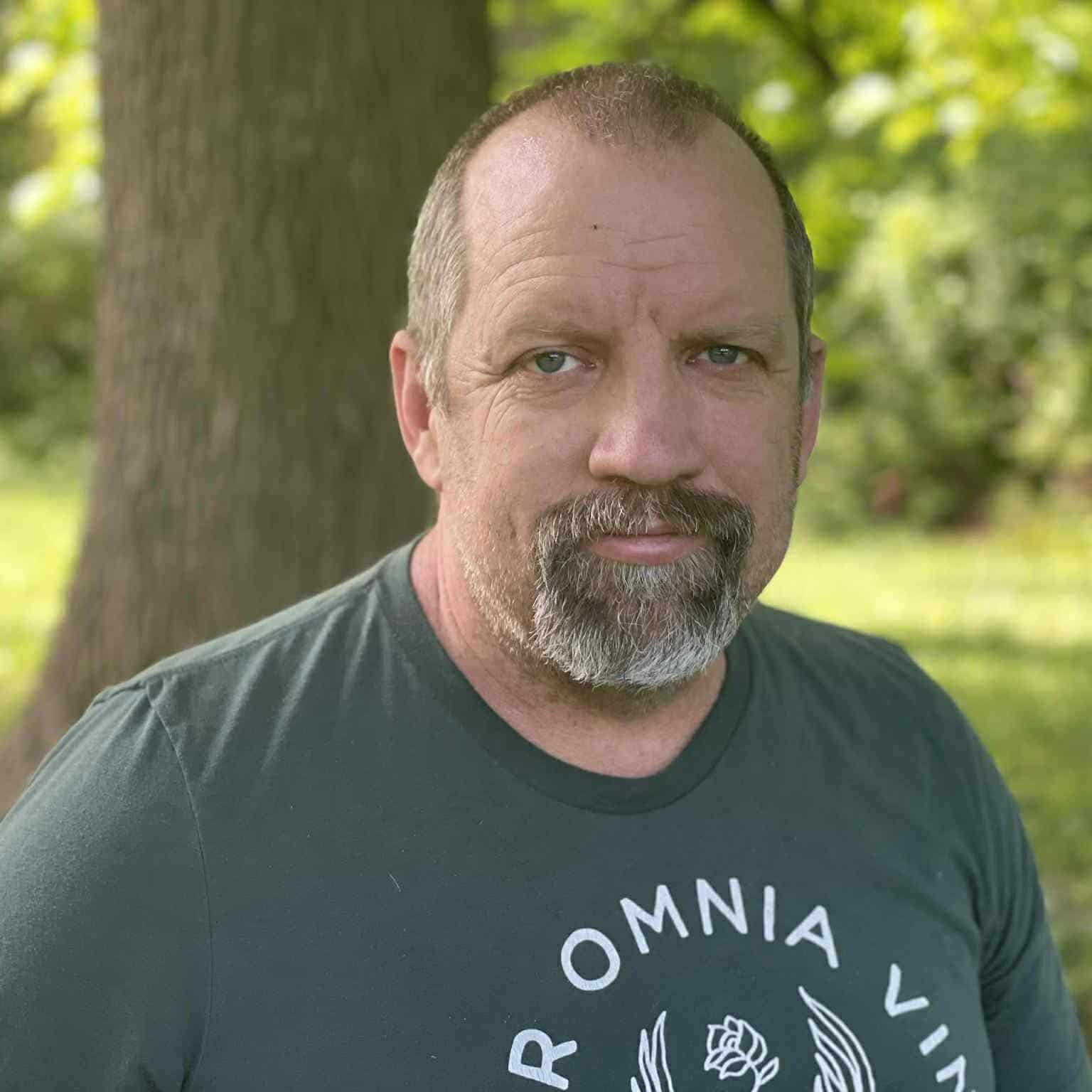

Konstantin Tatarkin, veteran, IREX veterans advisor

A column is a type of material that reflects exclusively the point of view of the author. It does not claim objectivity and comprehensive coverage of the topic in question. The point of view of the editors of “Economic Pravda” and “Ukrainian Pravda” may not coincide with the author’s point of view. The editors are not responsible for the reliability and interpretation of the given information and perform exclusively the role of a carrier.